COMMENT: Electric vehicles (EVs) are undoubtedly the future of mobility. But, arguably, one key to increasing EV adoption might be using traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) nameplates and architectures.

Electric cars provide automakers an opportunity to radically rebrand, introduce new model line-ups, and drive a new design direction. However, full-electric models that are more familiar to ICE cars today might better drive EV uptake, especially in Australia.

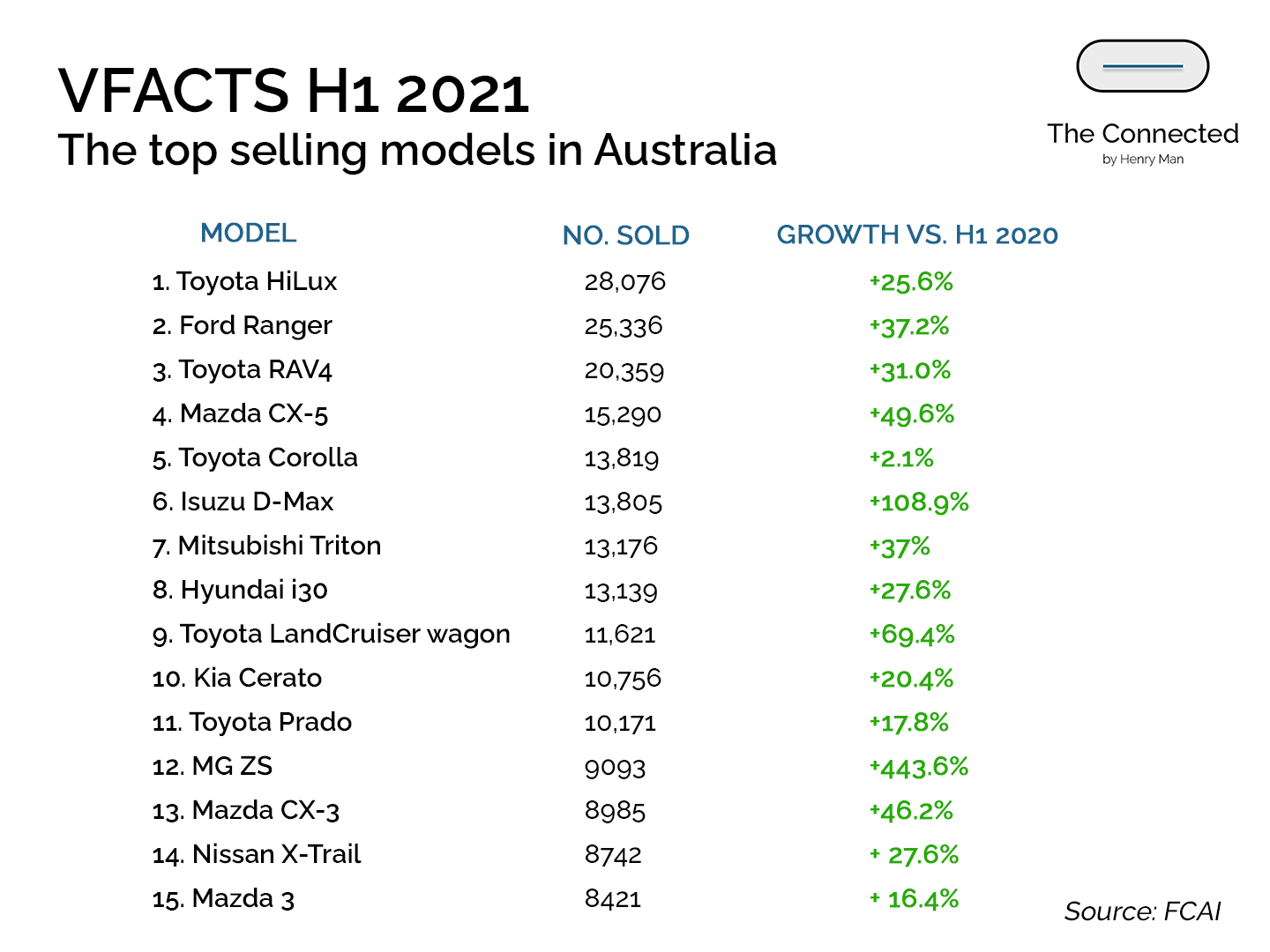

Think about the most popular models on our roads today. Figures from the Federal Chamber of Automotive Industries (FCAI) outline no surprises when it comes to the best selling models in Australia for the first-half (H1) of 2021.

Models like the Toyota HiLux, RAV4, Corolla and LandCruiser, Ford Ranger, Mazda 3, CX-3 and CX-5, Hyundai i30 and Kona, and more have enjoyed substantial growth compared to H1 2020.

Importantly, these nameplates have consistently remained on the top podium every month for at least the past three to 10 years. So, will consumer sentiments ever change and adopt all-new, foreign badges?

ICE-based EVs

The truth is: ICE cars today are fundamental to the growth of EVs. While price parity (i.e. EVs costing the same as ICE cars) will eventuate in around four years, they won’t be cars built on radically new – and expensive – dedicated electric architectures.

Consumers want familiarity. A well-known badge and design language, albeit electrified, is one key to drive demand, alongside political incentives and corporate initiatives.

ICE-based platforms, fake grilles, and existing badges might be the answer to democratising EVs, at least in the immediate future.

This strategy is already seen in the likes of the Volkswagen e-Golf (defunct), MG ZS EV, Hyundai Kona Electric, Peugeot e-208, Ford F-150 Lightning, BMW i4 and i4 M, Mini Cooper SE, Genesis eG80, Volvo XC40 Recharge Pure Electric, Lexus UX300e, Mercedes-Benz EQC, and more.

Toyota is the perfect case study. It has reaped success with the introduction of its series-parallel hybrid system as an option across almost its entire model line-up, from the Yaris city hatch, to the CH-R crossover, RAV4 medium SUV, and soon on the large HiLux ute, Prado and LandCruiser SUVs. They all use the same badge, design and equipment; just electrified.

Toyota Hybrid dominates. It now outsells petrol-only powered models, with more than 200,000 hybrid cars sold in June 2021 Down Under – half of which were sold in the past three years.

Yet, the firm’s hybrid tech has been featured on the venerable Prius sedan since 2001. The hybrid family subsequently grew with the Prius C hatch and Prius V wagon in 2012. However, they were never a roaring sales success.

That all changed in mid-2018 with the introduction of the twelth generation Corolla hatchback, offering the hybrid powertrain across all trim levels for a $1500 extra at the time.

Today, only the original Prius and Prius V exist – but they’re hanging by a thread with lacklustre sales. The Japanese automaker only sold 34 and 124 units in H1 2021 respectively.

By contrast, demand has outstripped supply for the RAV4 Hybrid, with customers waiting at least six months for the family SUV – and that’s without any impacts from the semiconductor shortage. It sold 20,359 units, majority of which were hybrid, in the same period.

Therefore, Toyota’s case study highlights the need for ICE-based full-electric cars. It is clear that most consumers want familiar models – not new, foreign nameplates with avant garde designs.

I personally dream of owning a Hyundai i30 Sedan, Ford Puma, or Skoda Octavia – but they need to be fully-electric. Forget about flat aerodynamic wheels, removing gaping grilles, and adding ‘blue bits’. The current EV offerings, admittedly, aren’t enticing enough for me; they’re unfamiliar and sometimes ostentatious.

If manufacturers want to drive EV adoption, simply make battery-electric propulsion an option for our ICE models today. By using ICE-based platforms, it will allow for price parity sooner and make the transition to emissions-free motoring more accessible.

Iconic nameplates

Using traditional ICE architectures for full EVs isn’t perfect, though. You can’t always afford the same benefits that a dedicated EV platform model brings like interior space, flexibility, and exterior design. That’s despite some ICE-based electric models allowing for front boots (frunks), big batteries, and 800-volt charging.

So, how can you strike the balance between selling a bespoke EV and enticing buyers? With the power of marketing, carmakers are utilising famous badges or even resurfacing their roots.

Ford has exploited its muscle car ‘pony’ moniker for the Mustang Mach-E SUV, even though it shares almost nothing with the hi-po petrol-powered Mustang coupe and convertible. Meanwhile, General Motors has revived back the iconic, robust GMC Hummer with the 2022 Hummer EV ute and SUV.

Mazda also utilises its ‘MX’ name, usually characterised with the sporty, lightweight MX-5 convertible, with the MX-30 Electric city SUV crossover that’s actually based on a Mazda 3 and CX-30. The new-generation 2020 Fiat 500e continues its iconic 1957 nameplate, albiet now as an electric-only model. Similarly, Opel is set to resurrect its famous Manta nameplate for an EV model soon, too.

These electric cars may be completely unrelated to their ICE siblings, but they can get more attention from prospective buyers and the media as they feature a familiar nameplate (sometimes controversially).

It’s all about marketing.

Radically new models

Some automakers have taken the experimental ‘Toyota Prius approach’. That is, harness the electric revolution and introduce new nameplates or entire model line-ups.

For instance, the new Hyundai Ioniq and Kia ‘EV’ family built on dedicated underpinnings, the ICE-based Kia e-Niro and e-Soul small SUVs, Nissan’s stalwart Leaf hatchback and upcoming Aryia SUV, the Renault Zoe city hatch, Volkswagen’s ID. and Skoda’s iV line-ups, the sleek Porsche Taycan coupe (despite keeping ‘Turbo’ guises), Jaguar I-Pace SUV, plus more.

Some manufacturers take a median approach by adding a few letters on their traditional internal combustion models, like the ‘EQ’ designation for all-electric Mercedes-Benz models, ‘e-Tron’ for Audi, an ‘i’ or ‘iX’ for BMW, or a simple ‘e’ for most Stellantus group models.

Some, of course, are bound by their own brand as relatively new electric-only companies, including Tesla, Polestar, Xpeng, Nio, Lucid, and Rivian.

For Norway, where EVs have become mainstream, they’re successfully buying new nameplate models in droves.

But, the question remains: As carmakers transition to producing only battery-electric models from 2025 to 2040, will sales charts, especially in Australia, dominate with entirely new nameplates or will consumers keep buying traditional ICE badges we’ve come to know?