Smartphone prices have more than doubled in a decade, yet essential accessories aren’t included anymore – and the trend doesn’t seem to end as more essential services moving online.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story was produced as part of a major project for the Data Journalism (JOUR3000) course at The University of Queensland.

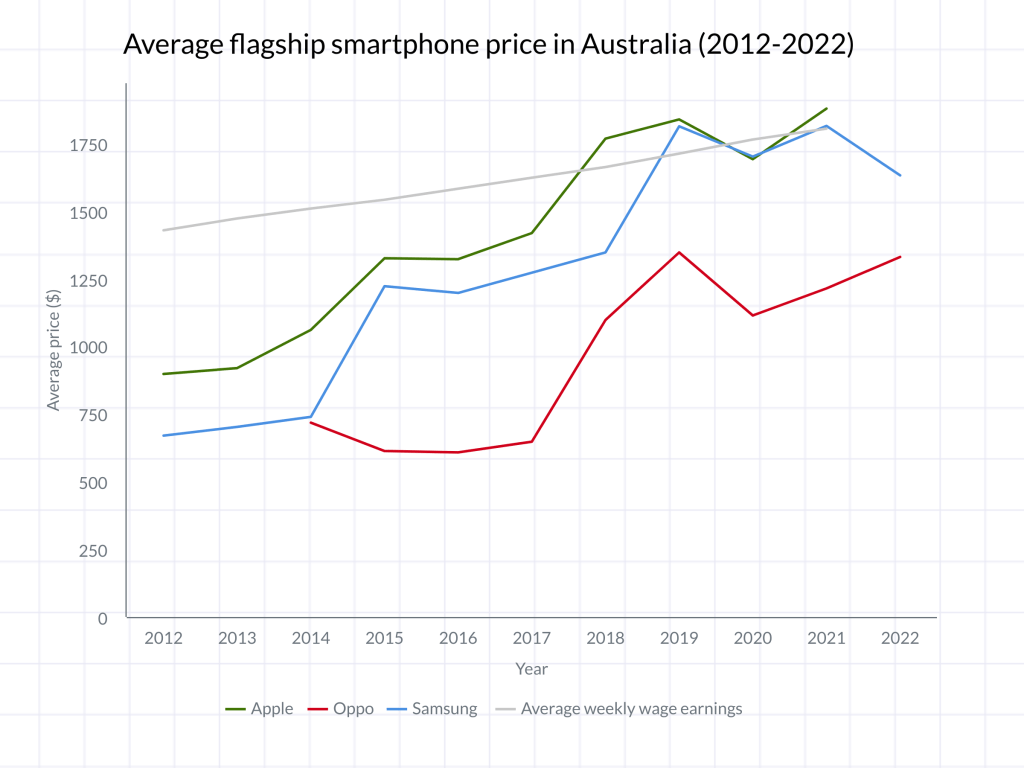

Data collected by Henry Man of the top three most satisfied phone brands in Australia (Apple, Oppo and Samsung), according to Canstar Blue’s most recent survey, reveals prices have skyrocketed by an average of 112 per cent in the past 10 years.

No data has been previously publicly recorded on the growing trend of smartphone prices.

Today, Australians can buy a phone anywhere from $200 to $3000 depending on the brand and capabilities like cameras, processors and materials.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), typical weekly incomes can just afford the average price of a flagship Apple or Samsung device, though Australians today are also facing increasing cost of living pressures with inflation growing at its fastest pace in 20 years.

For example, the Samsung Galaxy S3 in 2012 cost $899, whereas the entry Galaxy S22 flagship is now priced from $999 with its halo Galaxy Z Fold3 foldable model going up to $2449 in 2022.

Even budget-orientated manufacturers like Oppo have gradually become more expensive. When the brand first launched in Australia in 2014, an Oppo Find 7 cost $719, but today’s latest Find X5 Pro flagship fetches for $1799.

Meanwhile, an Apple iPhone 5 was priced from $799 in 2012, but an iPhone 13 mini today now starts from $1199 or the most expensive iPhone 13 Pro Max from $1849. Opting for the highest one terabyte storage increases the latter to $2719.

Technology commentator Geoff Quattromani said Apple iPhones are problematically the default choice for Australians when buying a new smartphone, especially for consumers who lack technology literacy.

“I was spending a lot of time answering people’s calls through talkback radio about what the right device was that they should buy – talking about the [midrange] Samsung A-series, Oppo, Nokia and so many brands that have cameras, run Android and do the same stuff that they actually need it to do, which is critical,” he said.

“It’s the older generations. There are a lot of people out there who didn’t have a smartphone or maybe it’s six years-old because it was handed down through multiple people before it got to them.

“It was very interesting during the start of the pandemic because the default mindset was that they would need to spend $1000 on a phone.

“When you tell somebody that you need to get a smartphone, for a lot of people it means getting an iPhone.

“That’s a problem because it’s an expensive device and they don’t even really know why they need it. They just need to scan a QR code once, but they don’t need to spend $1000 to do that.”

In the past decade, smartphones have significantly improved their hardware and software capabilities with the introduction of 4G and 5G connectivity, bigger screens, larger storage capacities, additional camera lenses and more powerful processors.

Singaporean international university student Kevin Goh believes smartphone prices have become too inflated, but concedes he still bought a flagship smartphone.

“It’s a long-term investment, not just from the aesthetics perspective but because of the performance,” he said.

“Don’t keep something in the midrange and then regretting it two years later. Buy something that lasts three to four years.

“It’s a device you touch every day. Everything you do is probably linked to a smartphone, so always spend more on a device that you interface with the most on a daily basis.

“Having said that, you may not have the discipline to hold onto a phone for a long period of time, but it is better for most consumers to buy a phone that lasts longer, for me included.

“Admittedly, I’m a bit biased. Do I really need my phone to be so fast? Am I saving seconds? Is it really adding value in the long-term? Probably not.

“Not everyone can afford an expensive phone. It’s a luxury product. It’s not necessary. I’d rather buy a laptop.”

Excluding mobile necessities

An increasing number of technology giants are also excluding out-of-the-box essentials like charging adapters and earphones to reduce e-waste for environmental sustainability, but Mr Quattromani believes this is a greenwashing tactic.

“It looks good. Probably shareholders appreciate it, maybe some members of the press, maybe there’s some people out there who think it’s a good thing,” he said.

“However, if someone changes their phone every four years, that old power adapter is most likely not going to have the same power output as a new one today. That’s not fair.

“The other part where they’re being cheeky is, by taking the charging brick out of the box, the box is now half the height.

“That means you can now pack probably twice as many iPhones into a box, twice as many boxes onto a palette, so it actually reduces their shipping costs.

“Maybe there’s an environmental factor they could use as an excuse too, but they’ve saved a lot of money on shipping, by not having to produce power adapters, and they’re also making money by selling them in the store if you need a new one.

“I don’t support it, especially when the risk is for someone to go to a market and buy a very dodgy non-certified power adapter.”

Digital transformation

The COVID-19 pandemic has also encouraged consumers to buy or upgrade their smartphones with the acceleration of digitalising essential services like banking, welfare and health, while virtually communicating with others, previously mandating check-in QR codes, and presenting vaccination certificates.

According to the Broadband Advisory Council, COVID‐19 has brought forward 10 years of growth in data consumption, with smartphone use dominating at a 38 per cent increase compared to personal computers at 23 per cent.

Digital transformation researcher Associate Professor Stan Karanasios from the Business School at The University of Queensland said mobile technologies have become an everyday necessity.

“We are now really at the forefront of the digital revolution. The way organisations do things is increasingly driven by technologies, which has been accelerated by COVID-19 because there was no other option,” he said.

“The smartphone is now more integral to our everyday functioning, but with Apple or Samsung saying, ‘well we know that this device is now something you can’t live without’, there is a greater demand for these devices and people may be more willing to pay for a smartphone.

“There is also a limited amount of rare earth minerals, supply chains have taken a beating over the past few years, there is a global chip shortage and that just drives prices up.

“For people in the developing world who can’t shell out the extra $300 or $400, the smartphone is also very integral, so the concern is that we may have a growing divide between people who can afford the latest and the people who have something with a lot less punch and features.

“But we could do better with ensuring equitable access around the world as there are still a number of people who still can’t gain access to the Internet and enjoy its benefits.”

The new social divide

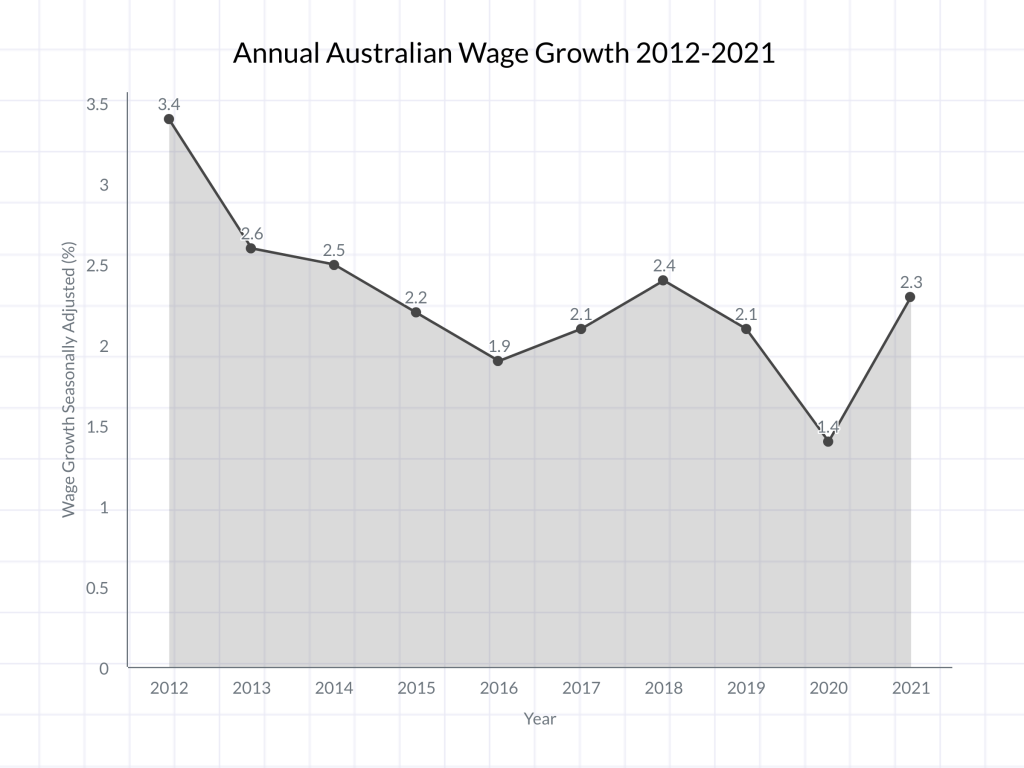

Despite significantly rising phone prices, annual wage growth has remained stagnant, declining by 1.1 per cent between 2012 to 2021 according to the ABS.

Mr Quattromani believes expensive smartphone brands have become the new status symbol, which is creating a social divide especially among younger Australians.

“One of the big things I remember when I was in school was everyone had the same school uniform, but Jeremy turns up with a pair of Nikes, I’m turning up with a pair of cheaper sneakers. Jeremy is the cool kid,” he said.

“What we’re seeing now is sneakers probably still plays a factor, but what smartphone they pull out at lunch time I think now plays a bigger role.

“The parents who are happy to spend $1000 to give their kids an iPhone is creating a social gap to the next student whose parents didn’t gave them a cheaper device like an Oppo.

“It still does the same things as the student needs it to do, but the fact that somebody has an iPhone over another student does create a social problem.”

While there was usually one flagship device choice for consumers in the past, tech companies have expanded to offer entire line-ups separated by lesser equipped and top-spec models.

Mr Quattromani said in consumers’ mobile purchasing decisions are now driven by personal fashion statements to gain a perceived elevated status.

“It’s the same a swearing a fancy watch or wearing fancy sneakers. Apple’s created it. The pro iPhone is a nicer looking phone. It’s got the steel edging and that obvious third lens,” he said.

“If someone wants to take a group photo, people look around, say ‘that one’s the pro’ and they grab it for no real reason.

“That lens is for optical zoom. It’s not actually going to help improve that group photo.

“I’ve seen it in so many group situations. Someone sits down at the table, pull their keys out, their phone on the table and people ask ‘hey, is that the new iPhone?’ or ‘is that the new Samsung?’

“That is a massive flex that everybody is doing and knows that they’re doing subconsciously or not.

“That’s what we’ve created. It’s a status symbol. It’s not about capability anymore. A lot of people probably just don’t pay attention to it, but it’s a very real problem.”